Salmonella caught red-handed (Article MaxPlanckForschung)

Salmonella research provides clues to antibiotic development

New ways of developing urgently needed antibiotics against pathogens - this is what scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology and of Biochemistry, in co-operation with colleagues at Hannover Medical School have discovered. But their findings have bittersweet implications: it turns out there are fewer possibilities for producing antibiotics than had previously been hoped. The results point the way for future antibiotic research. (Nature, March 16, 2006)

Pathogens are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics, causing problems for therapy. Doctors need to have antibiotics available that work in new kinds of ways. The last few years of research have, however, found few such ways. One major difficulty for developers of antibiotics is choosing the proper point of attack against bacteria. There are hundreds of possible points of attack, according to genome analysis and laboratory culture experiments - but validation in in vivo infection models is largely lacking.

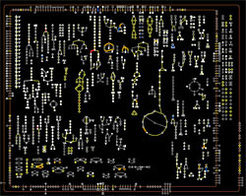

Infection biologists and proteomics researchers have now identified all the proteins involved in Salmonella metabolic paths during an infection. Dirk Bumann of Hannover Medical School led a team including Daniel Becker, Claudia Rollenhagen, Matthias Ballmaier and Thomas Meyer of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology. They isolated Salmonella from infected mice. Proteomics researchers Matthias Selbach and Matthias Mann from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry then turned to highly-sensitive mass spectrometry to look at the protein mixture - and discovered hundreds of different Salmonella metabolic path proteins. The scientists compared them with special protein databanks and identified possible points of attack for antibiotics.

Bumann and his team then examined what role these proteins play in a Salmonella infection. The scientists turned off genes responsible for the proteins to see how it affected the disease’s progress. "Knocking out" the gene was equivalent to blocking its corresponding metabolic path, thereby simulating the effect of antibiotics. The analysis demonstrated the following: in the two possible types of salmonella-related illness (diarrhoea and typhoid), the bacteria is surprisingly unaffected by the blockade of several central metabolic pathways. The reason for this is redundant enzymes, as well as the host offering a wide range of nutrients, which means Salmonella does not depend on its own biosynthetic abilities.

Only a few enzymes in certain metabolic pathways are really necessarily to keep Salmonella bacteria alive. Most of these essential enzymes are missing in other important pathogens, or they are also present in the human organism, so they cannot be considered possible points of attack for new broad-spectrum antibiotics with a wide range of effectiveness. The remaining potentially useful metabolic paths are already used as the targets of current antibiotics - or have already been considered for development of an effective antibiotic.

A comprehensive analysis of two infection models - typhoid and diarrhoea - shows clearly that there are far fewer than expected possible points of attack for developing urgently needed antibiotics. It is also now obvious that increasingly ineffective antibiotics ought to be replaced by similar, but not identical, active principles. This points the way for future antibiotic research.